The 70s

|

|

|

Julião Sarmento, Faces (detalhe), 1976. Filme Super 8, cor, sem som, 44´22´´, dim. variáveis. Col. Van Abbemuseum.

José Manuel Costa Alves.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Eduardo Luiz, O 7º disfarce de Zeus, 1972. Óleo sobre tela, 194 x 113 cm. Col. Centro de Arte / Col. Manuel de Brito.

DR/ Cortesia Galeria III.

|

|

On the eve of the 1974 Democratic Revolution, Portugal was presented with a very complicated state of affairs. To begin with there was a colonial war that was sustained for too long and with no visible solution. The belated and ineffective openness of the political system, a feeble attempt by the administration of Marcelo Caetano since 1968, and the deterioration of the institutional structures of the Estado Novo (lit. "New State") whose political core was powerless to bring a way out of the stalemate in which Portugal found itself, generated a government deep in the agony for survival and extremely weakened under the eyes of the international community. Secondly, a generalized dissatisfaction and the social and economic difficulties of the population characterized the isolated reality of a country that still mirrored itself in the famous Salazar adage, "Proudly Standing Alone", guided by a class dependent upon obsolete political and ideological values.

Within this framework, battered by the regime's long life, Portuguese society suffered the negative effects of political interference in the dynamics of culture. The relative openness of the system in the regime's last years only underlined and made more visible the perception of the abyss that separated the social and artistic reality of Portugal and the contemporary international dynamics.

Notwithstanding, one must not believe that nothing existed before the 25th April 1974 Revolution (a democratic military coup d' etat) and neither that everything became possible and successfully so. Actually the lack for adequate cultural policies was unvarying and persistent.

Within the artistic context, more specifically the visual arts sphere, the ideological, political transition period that the country went through in the 70s produced a complex multiplicity of references, which indirectly contributed towards the opening of a new juncture of the cultural and artistic activities.

If one cannot deny that Marcelo Caetano administration's reforms allowed for a more effectual openness to the international scene, one cannot forget that the basic cultural policy was characterized by an institutional inefficiency. This was verified by the lack of museums or centres for contemporary art, by the fragility or total inexistence of a specific market and by the almost complete absence of State endowments to contemporary aesthetical actions.

Nevertheless, with the new economic measures of Marcelo Caetano's government, besides the many commissions for the headquarters of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the creation of the Soquil Awards (1968-1972), one can say that the art market began to give signs of some vitality. As for instance with the emergence of a clientele that became more aware and attentive towards modern art, in detriment of a deep-seated, 19th century-informed judgement. The period of high speculation on the value of works of art around 1973 was not enough to say that there was any sort of effective, consistent market dynamics.

Such a diminutive boom of the art commerce in Lisbon and Porto was translated into the proliferation of many galleries or other exhibition spaces. By the end of the 60s and throughout the next decade, the galleries Zen (1970) and Módulo-Centro Difusor de Arte (1975) opened in Porto, Buchholz (from 1965 at Duque de Palmela street), Dinastia (1968), Judite da Cruz, S. Mamede (1969), Quadrum (1973) and the second Módulo Gallery (1979) in Lisbon, and Ogiva in Óbidos (1970). In addition to the exposure and formation of several artists by these galleries, especially by the Quadrum and the Ogiva Galleries which promoted a movement of decentralization, the CAPC (Círculo de Artes Plásticas de Coimbra - Circle for Visual Arts in Coimbra) assumed an important role in the experimentation and promotion of new aesthetical attitudes with events as critical as Minha Nossa Coimbra Deles (Theirs Mine Ours Coimbra, 1973), Arte na Rua or 1000001º Aniversário da Arte (Art on the Streets and 1000001st Anniversary of Art, both in 1974) . These symbolic "happenings" and "performance" acts aimed to call people's attention towards the fact that the institutions lacked thoughtfulness, as well as to generate the required conscience for the work to be done ahead.

|

|

|

|

Sá Nogueira, Erotropo, 1970. Técnica mista sobre tela foto-sensível, 77 x 121 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

DR/ Cortesia Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

|

|

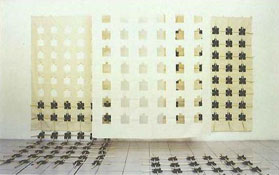

Pires Vieira, Des-Construções, 1974. Tela de algodão, esmalte sintético, corda, dim. variáveis. Col. Fundação de Serralves.

Catarina Costa Cabral.

|

| |

|

| |

Nikias Skapinakis, Encontro de Natália Correia, Fernanda Botelho e Maria João Pires, 1974. Óleo sobre tela, 140 x 110 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

DR/ Cortesia Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

João Cutileiro, Maquete de D. Sebastião - I, 1972. Mármore, 46 x 15 x 15 cm. Col. particular.

João Cutileiro Jr.

|

| |

|

The restructuring of the Portuguese chapter of the Art Critics Association (AICA) in 1969 was of vital consequence but far more important was the emergence of the critical, modernized discourse of Ernesto de Sousa. A critic, curator and artist, Ernesto de Sousa was a controversial figure then, who developed a strategy of ruptures and discontinuities in relation to the established canons. After a phase dedicated to cinema and neorealist aesthetics, Sousa chose the path of experimental art of a strong conceptual vein, in close harmony with what was being done abroad. He visited the 1972 Kassel Documenta, where he would meet Joseph Beuys and came across directly with Harald Szeemann's ideas. This would then deeply mark his critical thought and contribute to bring new issues to the national stage such as the dematerialization of art, the notion of "open-ended work", of the artist as an "aesthetic operator" and of the active role of the spectator. As a curator and promoter of projects, we should highlight his Encontros do Guincho (Meeting at Guincho, 1969), Nós não estamos algures (We are not Somewhere, 1969), O meu corpo é o teu corpo (My Body Is your Body, 1971) and the exhibitions held within the framework of the AICA, such as Do Vazio à Pró-Vocação (From Emptiness to Pro-Vocation, 1972) and Projectos-Ideias (Projects-Ideas, 1974). We should also mention the decade's historical milestone: Alternativa Zero (Alternative Zero, 1977).

The deaths of Eduardo Viana (1967) and Almada Negreiros (1970) and the first major retrospective of Vieira da Silva in Portugal held at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (1970) are the take-off, as it were, for a new period of the scene of Portuguese art.

In the first half of the 70s there were some new magazines appearing: Colóquio- Artes (1971-1997), whose director was José-Augusto França; in Porto, in 1973, the Revista de Artes Plásticas was put out. The following year, José-Augusto França sees his A Arte em Portugal no Século XX (Portuguese Art in the 20th Century) published, a reference work for the national artistic historiography. Also in 1973 - the year Picasso dies - there were three other major events that we must mention.

During April an exhibition called 26 Artistas de Hoje (26 Contemporary Artists) gathered at the Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes (SNBA) some of the works by the artists who had been the recipients of the Soquil Award.

In September of the same year, in Lagos, Algarve, the Cutileiro's monument to Dom Sebastião was inaugurated. It is not easy to find another figure who, through its sheer historical, cultural and mythical clout, expresses more perfectly the atmosphere of nostalgia and of awe for the past that hindered the whole Portuguese society for so many decades. At the same time Dom Sebastião was also one of the most inspiring figures for the irrational, reactionary, inactive and melancholic attitude that for such a long time characterized the most influent currents of though in Portugal. These few historical and cultural considerations will cast some light upon the importance one must give to João Cutileiro's statue of Dom Sebastião and why we consider it to be one of the key-works of the period. From his technical experience with "articulated dolls", the sculptor produces us the young king depicted as a small boy who questions the Imperial Portugal myth, renovating and raising at the same time the boundaries of Portuguese statuary, dethroning forever the regime's sculptoric tenets, whose head-figure was Francisco Franco. The physical presence of this statue at a plaza in Lagos is associated to the gesture with which the adolescent Sebastião places his helmet on the ground and offers his clear, open gaze to his surroundings and through which his body becomes absorbed by the light.

|

|

|

|

|

|

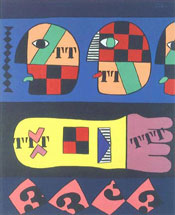

José de Guimarães, Máscara com Tatuagens, 1973. Acrílico sobre tela, 100 x 81 cm. Col. Museum Würth.

José Manuel Costa Alves.

|

|

Eduardo Batarda, What´s in a nose?, 1973. Aguarela sobre tela, 77,3 x 58,8 cm. Col. Banco Privado Português.

DR/ Cortesia Banco Privado Português.

|

|

João Abel Manta, MFA - Sentinela do Povo. Postal, sem data. Col. Museu da Cidade - CML.

DR/ Cortesia Arquivo Fotográfico do Museu da Cidade.

|

There were other artistic events that announced the imminence of political changes in a more evident way. In December 1973, at the SNBA, the Exposição 73 is opened. Right in the hall one found a realistic sculpture of a dead soldier, with the uniform used in the colonial wars its title is Jaz Morto e Arrefece (Laying Dead and Getting Cold), and Clara Menéres is the author. Behind this sculpture, a frieze of silent, stone-dead faces in a painting by Rui Filipe. During the night of the opening, a performance by Joao Vieira, which showed a naked woman painted in gold, became a small scandal. The 25th of April of 1974 witnesses the "25th of April".

.

In the following June 10th, Portugal's National Day, forty eight artists gather to commemorate the date and paint a huge panel, simultaneously and in front of a great audience and television cameras, The theme is freedom. This was a somewhat naïve event, a little comical even, but we cannot deny its emotional and contextual authenticity. During the film shoot, someone approached Júlio Pomar and tells him that his painting is complicated. He replies by saying that life is complicated too.

|

|

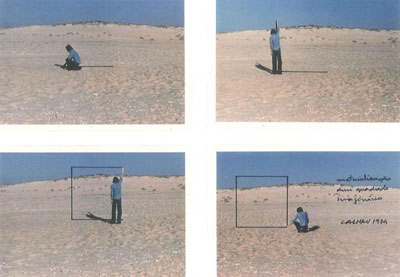

Fernando Calhau, S/ título, # 99. Materialização de um quadrado imaginário, 1974. Fotografia a cor e tinta da china sobre papel fotográfico, (4 x) 8,5 x 12 cm. Col. Fundação de Serralves.

DR/ Cortesia Fundação de Serralves.

|

In Porto, a "commission for a dynamic culture", which gathers visual artists, writers and poets, organized on the same day the Funeral for the National Museum Soares dos Reis. This protest - that assembled around 500 people - was aimed at the Portuguese Museum system in general, which was utterly obsolete.

The political events of 1974 interrupted the rhythm of the visual arts exhibitions, as well as the related critical work. There are almost no references whatsoever to artistic practices in the newspapers, although the inevitable enthusiasm triggered by the political uproar determined, even if fleetly, a certain renewal of cultural participation, in which a new relationship between artists and the general public was at least hinted at.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Clara Menéres, Mulher-terra-vida, 1977. Acrílico, terra e relva, 80 x 270 x 160 cm. Vista da instalação na exposição Alternativa Zero, Galeria de Belém..

Clara Menéres.

|

|

As it is usual in periods of political turmoil, whether pre- or post-revolutionary, many artists and cultural practices were instrumentalised by the basest, most anachronic and absurd of ideological manipulations. If we have to salvage something through aesthetic criteria from the whole political disturbances we should mention João Abel Manta´s cartoons and the magnificent street murals created by the MRPP party members, most of them having been destroyed in the meantime.

As for the aesthetic choices of these years there were continuous and simultaneous discussions of the dialectics between figurativism and abstraction, between painting and conceptual art (or post-conceptual actions) and there was a rethinking of the artists' intentions, now free from portuguese surrealism and neorealism and from censorship. It was in the new proposals being pursued abroad from the various strands of conceptualism to the post-avantgarde trends that artists sought a direction for a renewal or for more evident references for contemporaneity. Between the gridded rules of conceptualism and neo-figurativism, the aesthetic proposals of the 70s were rebalanced especially towards a growing consolidation of the individual paths of each and every artist.

Amongst these many questionings and revisions of modernity there were some important exhibitions from retrospectives to thematic shows, naturally related to the political and social situation of the country (for instance, the exhibition Pena de Morte, Tortura, Prisão Política - Death Penalty, Torture, Political Prison - held at the SNBA in 1975). Many pluralistic practices and intentions were publicized, which revealed not only a multiplicity of what was available, as well as the harmonious conviviality between different generations of artists, different styles, dynamics and references.

| |

|

| |

Vitor Pomar, S/ título, 1979. Acrílico sobre tela, 340 x 200 cm. Col. Caixa Geral de Depósitos. .

Laura Castro e Caldas e Paulo Cintra.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Ana Hatherly, As Ruas de Lisboa, 1977. Colagem, 110 x 90 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

Mário de Oliveira.

|

| |

|

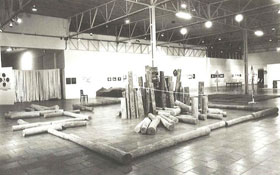

Within the visual arts, a major exhibition meant an ending to the period of the post-revolutionary turmoil, which served as a reflection upon the whole previous decade where the most avant-garde artistic experiences were concerned. We are referring to Alternativa Zero, at the Modern Art National Gallery, in Belém, 1977.This exhibition was organised by Ernesto de Sousa and it functioned as an assessment of the works that, within Portugal, had revealed a wider, closer harmony with the evolution trends, internationally speaking, of contemporary art. According to the words of the descriptive catalogue, the spectator was alerted to the fact that this event "wishes to be 'much more' that an exhibition: or to put things in another perspective, it wishes to become an open-ended exhibition with all the possible consequences within 'this' society, including the drive (even if only to a small extent) to transform it". The conceptual proposals by artists such as Alberto Carneiro, Clara Menéres with Mulher-Terra-Vida (Woman-Earth-Life) and João Vieira's video, were the example and proof of the exhibition's pluralistic line of thought, in a time when the absence of an art market deprived Portuguese works of a more effective or even real visibility. The exhibition titled Alternativa Zero - Tendências Polémicas na Arte Portuguesa Contemporânea (Alternative Zero - Polemic Tendencies in Contemporary Portuguese Art) was thus the first presentation of works of art that in Portugal had as models corresponding conceptual attitudes. However a minor and marginalized situation, it would be from this event that a first wave of artists would assume a preponderant role throughout the 80s.

In 1978, we have the first edition of the Art International Biennial of Vila Nova de Cerveira. This was an initiative that privileged contemporaneity in the first editions, which promoted artistic decentralization, which revealed curious cultural asymmetries and that made possible the temporary coexistence of the locality's own regional expressive traditions and the newness of the exhibited artistic forms.

Perhaps it was under the influence of this first Biennial of Vila Nova de Cerveira that the Secretary of State for Culture organised in 1979 the first edition of the Drawing International Biennial. In 1981 this event would be cut short abruptly, due to a fire in the Belém Gallery. Although it was not continued, one must underline its importance for the fact its gallery presented some of the works that crossed the boundary of drawing and reached an original experimentalist freedom using paper and its potentialities as their support.

The 70s was also the stage for the upholding of many visual languages that had been developed by artists in the previous decades but in many respects it radicalized some of the options developed in the 60s and it presented and consecrated a number of authors that demonstrated to possess very mature visual options. Among these artists, some of which consolidated their presence in both their critical reception and the art market of the time, we should refer the names of Júlio Pomar, Paula Rego, Joaquim Rodrigo, Mário Cesariny, António Sena, Álvaro Lapa, José de Guimarães and Eduardo Batarda.

Through the continuation of the researches of the previous years, namely in the field of concrete poetry, the highlight belongs to the eclectic work of Ana Hatherly, who made drawings, paintings, performances, happenings (such as Rotura - Routure in 1977) and cinema (Revolução - Revolution - in 1975). As an example, her participation at the Alternative Zero with Poemad'entro.

Within the field of painting, Luísa Correia Pereira, through her watercolours, collages on paper and other supports and techniques, elaborated an oeuvre whose main traits are a spontaneous representation and the bright chromatics with references to places, characters and objects from the imaginary worlds and more recently with references to the artist's own childhood. Vítor Pomar, who is strongly influenced by Zen Buddhism, used a two-colour aesthetic in his painting, mainly black and white, inscribing his work in the domain of abstractionism, but he also worked on photography, video and experimental cinema.

|

|

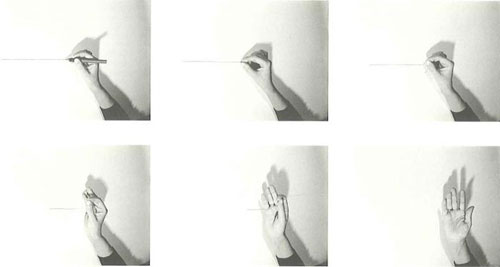

Helena Almeida, # 1 Desenho Habitado, 1977. 6 fotografias a preto e branco, tinta e colagem de crina, 42 x 52,2 cm (cada). Col. Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento em depósito na Fundação de Serralves.

Laura Castro Caldas e Paulo Cintra.

|

There were other artists who pursued paths at the margin of more traditionalised disciplines, such as Alberto Carneiro. He began during these years his first "theatre-ambiences" with works as significant as O Canavial: memória-metamorfose de um corpo ausente (The Marsh: metamorphosis-memory of an absent body, 1968-1970), Uma Floresta para os Teus Sonhos (A Forest for your dreams, 1970) and Uma linha para os teus sentimentos estéticos (A line for your aesthetical feelings, 1970-71), not to mention other proposals, closer to land art, such as Operação Estética em Vilar do Paraíso (Aesthetical Action in Vilar do Paraíso, 1973). Helena Almeida shifts her work towards using different media, especially photography, in which self-representation and the notions of space and of the performative body become key-references.

António Palolo extends his work to film, video and installation, approaching neo-conceptualist tendencies, and leaving behind him his painting influenced by the pop art and the minimalism attitudes of the early 70s. Julião Sarmento turns to photography and film directing as well, although keeping up with his exploration of sexual themes, characteristic of his previous pictorial works.

|

|

|

|

Vista da exposição Alternativa Zero, 1977. Col. Fundação de Serralves.

DR/ Cortesia Fundação de Serralves.

|

|

Ana Vieira, Ambiente - Sala de Jantar, 1971. Técnica mista, alt. 2m x 3,12m x 3,12m. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

Carlos Azevedo.

|

Also inscribed in a conceptual language we come across the name of Graça Pereira Coutinho, who lived in London and who used natural materials (such as dirt, straw, sand, leaves, chalk), artisan-like methods, handprints, illegible words, doodles, and many memories from her personal experiences, in order to create solutions that hover between sculpture and painting. On a different conceptual path, specifically exploring the concept of the work of art and its reception and divulgation mechanisms, we find Manuel Casimiro, who lived in France at the time. His was a work that was opened towards the image archive of the history of art having as its protagonist an egg-shaped form whose importance would grow from the 70s onwards.

José Barrias, who lived in Milan since the 60s, being quite conscious that the 70s was a period in which techniques could be converged and blended, began to develop several thematic cycles in the field of visual arts in conjunction with his more theoretical work. Ana Vieira was another artist who researched the interchange of genres, especially through her installation-ambiences done throughout the 70s, in which the spectator assumed a central role, whether for the fact he or she was invited to participate or because he or she was barred from entering the spaces created by the artist.

|

|

|

|

Pedro Calapez, S/ título (detalhe), 1982. Grafite sobre papel, 280 x 150 cm. Col. Maria de Belém Sampaio.

José Manuel Costa Alves.

|

|

Related with post-minimalism, we have the works of Fernando Calhau and Zulmiro de Carvalho. The latter explored in his sculptures the very plasticity of materials such as wood, iron and stone. Fernando Calhau adopted certain op(tical) values and developed many works closer to conceptualism via photography and film.

Pires Vieira is another artist who demonstrated a certain minimalism propensity in his paintings of the 70s, exploring in the first years of that decade on pure colours and later on turning to issues related to the “deconstruction" of painting, its decomposition in structures and the very processes of elaboration. All these actions resulted in canvases that were hung with no framework and with cut-out, patterned geometrical forms.

Where collective action is concerned, the 70s were characterised by a festive and utopia-tinted feeling characteristic of its socio-political context. It witnessed a number of projects, some of which were already referred to, as well as the founding of new artists' groups that shared a certain set of artistic and social goals, namely the convergence of several disciplines (with reminiscences of the Fluxus movement), the refusal of any sort of academicism and social and political intervention. In this context we can mention the Acre group, formed in 1974 by Clara Menéres, Lima de Carvalho and Alfredo Queiroz Ribeiro, who acted out events such as painting the pavement of Rua Augusta in the centre of Lisbon and/or the distribution of artists' diplomas - as Piero Manzoni did - at the Opinião Gallery. More directly associated to painting and performance, the Puzzle group, which worked between 1975 and 1980, developed many issues related to the social function of art and the artist.

|